In 2024, I set the goal to learn more about designing for human-centered AI and would love to share my learnings from reading academic papers in the field as part of the journey. The hope is to make knowledge in design, behavioral science, and human-computer interaction friendly and accessible for everyone.

In this blog post, I’ll share my review notes for the paper AI Alignment in the Design of Interactive AI: Specification Alignment, Process Alignment, and Evaluation Support by Michael Terry, Chinmay Kulkarni, Martin Wattenberg, Lucas Dixon, and Meredith Ringel Morris. 2023. arXiv:2311.00710.

User Interface Shifts in Computing History

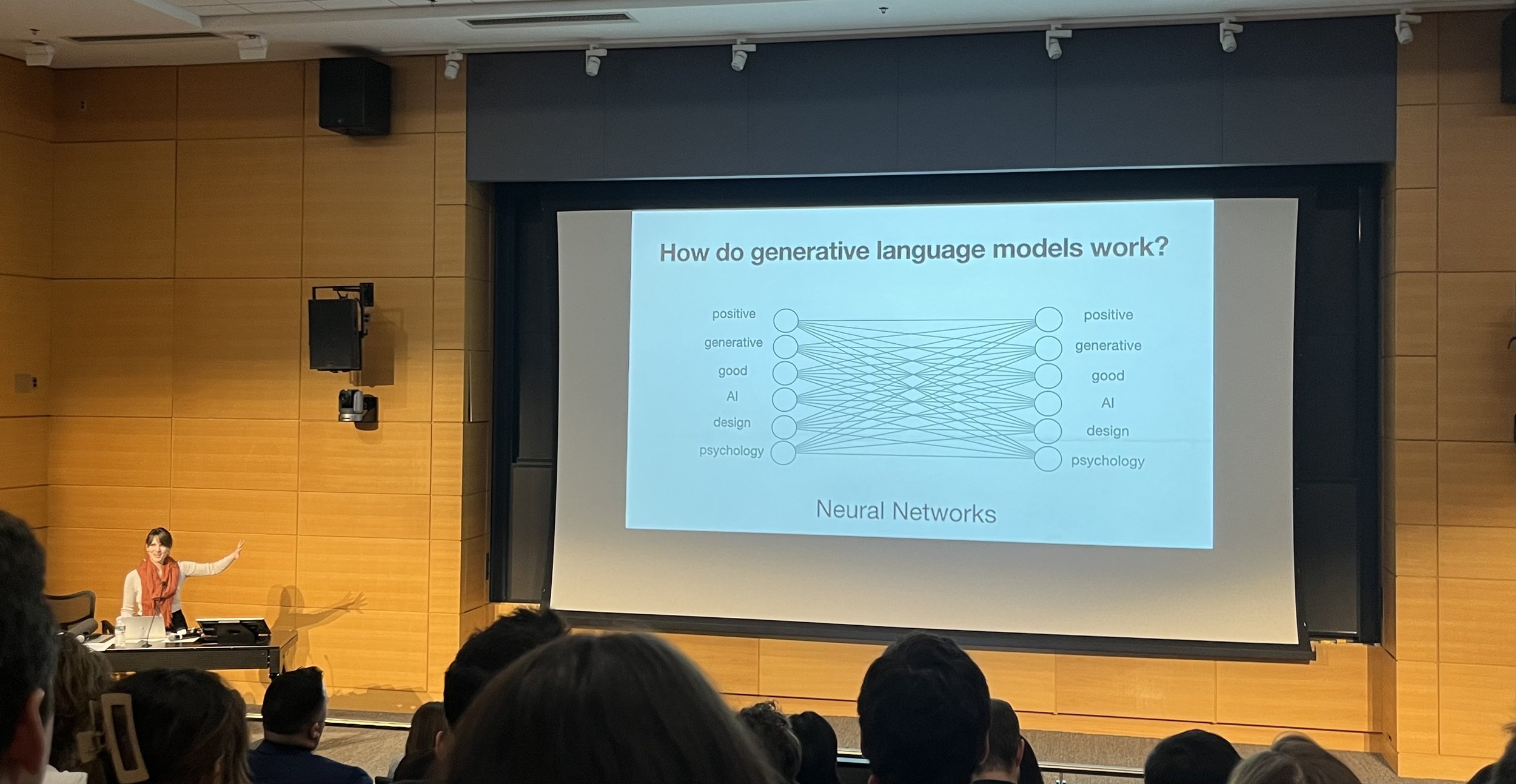

For those who are unfamiliar with user experience (UX) or human-computer interaction (HCI), here is a high-level overview of how user interfaces (UI) have evolved in the past 60 years:

Batch processing: The first general-purpose computer was introduced around 1945. The UI was a single point of contact where people needed to submit a batch of instructions (often a deck of punched cards) to a data center, then they would pick up the output of their batch the next day. It was common to need multiple days to fine-tune the batch to produce the desired outcome.

Command-based interaction: Around 1964, the advent of time-sharing (multiple users sharing a computer’s resources for tasks) led to command-based interaction, where users and computers can take turns, one command at a time. In particular, graphical user interfaces (GUI), using visual elements that convey information and actions a user can take, have become the dominant UX since the launch of the Mac in 1984. A strength of GUI is that it shows the status after each command if designed well. Users don’t need to have a fully specified goal initially because they can reassess the situation and modify their goal/approach as they progress.

Intent-based goal specification: With the third UI shift, represented by the current generative AI (e.g. ChatGPT, Gemini), the user tells the computer what outcome they want, but does not specify how it should be accomplished. Today, users primarily interact with the system by issuing rounds of prompts to gradually refine the outcome, which is a form of interaction that is currently poorly supported with rich opportunities for usability improvements and innovation.

From batch processing to command-based interaction, the speed of fine-tuning the desirable outcome improved drastically. However, with the third shift to human-AI interaction, the lack of transparency of how the AI performs a task, especially for the increasingly complex and high-consideration scenarios, presents new UX challenges for the HCI community today.

Photo by Falco Negenman on Unsplash

Interaction cycle for human-AI systems

The ultimate goal of human-AI interaction is to efficiently achieve a desirable goal for the user. Today, this process involves 3 basic steps: user input, system processing, and system output.

Different from the traditional command-based interaction, where a user monitors and gives commands at every step in the process, with an AI system, the user’s skills shift to focus on (1) being clear and effective at articulating the goal and providing input, and (2) once the output is available, being able to assess if their goal has been achieved.

As an analogy, a human’s role switched from being the executor (take main control to execute) to being the manager (tell another person to execute for you). It requires a different set of skills and mindset, just as when an independent contributor switches to a manager role. For a team to be effective, the manager can’t micromanage every step, otherwise, it decreases the overall productivity. In this case, what are the key touch points where humans (the manager) need to intentionally “align” with the AI system (the executor) to ensure the interaction is effective?

Overview of the paper

To ensure an AI produces desired outcomes, without undesirable side effects (also termed “AI Alignment”), Terry et al. introduce 3 dimensions to consider as we address user interface challenges with AI systems: Specification alignment, Process alignment, and Evaluation support.

Specification alignment is the first step in human-AI interaction, where the user defines the desired outcome for the AI system to execute. In addition, the paper also points out the importance of specifying constraints (e.g. safe, cost-effective, aligned with human values). As an extreme example, consider the paperclip thought experiment, where an AI is tasked to produce as many paperclips as possible. The AI may eventually start destroying computers, refrigerators, or anything made of metal to make more paper clips, which is not aligned with how humans will achieve the goal.

Process alignment refers to providing the ability for users to view and/or control the AI’s underlying execution process. The paper proposes providing mechanisms that ensure (1) the user can understand how the system executes the task in ways that can be understood by humans (“means alignment”), and (2) give users the ability to modify these choices (”control alignment”).

Evaluation support is the final step where users validate that the AI’s output meets their goals. As AI becomes increasingly capable of difficult and complex tasks, a significant challenge is evaluating its outputs. The problem of evaluation can be further divided into two problems: (1) verifying the AI’s output correctly and completely fulfills the user’s intent and comprehension, and (2) understanding the AI’s output, with comprehension being a much more important problem to solve.

Photo by Kiara Sztankovics on Unsplash

Personal notes

1\ Cognitive challenges with defining outcome. Counterintuitively, this step can be tricky because humans are not good at knowing or being able to describe what they want initially, especially for complex and high-consideration tasks. Considering human cognitive limitations, it’s important to account for the process for users to learn, then gradually understand and be able to describe their goal. This resembles a classic decision-making challenge when people shop. Although you know the goal is to buy a vacuum, you still need to go through the lengthy process of reading articles to learn about its major categories and functionalities and talking to friends and families before you know what you truly need and want. Similar to shopping research, the learning process is where we gradually build confidence in our judgment. Open question: how might we help users learn while maintaining efficiency in the process? One idea could be dynamic, personalized support for more or less explanation as users specify the requirement.

2\ Verifying interpretation upfront. One way to improve specification alignment for general-purpose AI is by providing the ability for users to verify and make necessary corrections to the AI’s interpretation of the intended outcomes before it proceeds. I love this direction because it resembles how real-life human collaboration works. Think about the manager and IC example, to ensure your project goal is aligned with what your manager has in mind (which could sometimes be under-specified or ambiguous), paraphrasing the requirement and sharing your plan of action beforehand helps confirm again that you and your manager are on the same page. Future research to understand (a) how real-life human collaboration and communication best practices can be applied for human-AI interaction, and (b) the right balance for efficiency vs. efforts for verification will be interesting to explore.

3\ Bridging the Process Gulf with a Surrogate Process. The paper introduces the concept of Process Gulf, as an extension of Norman’s concepts of the Gulfs of Execution and Evaluation, that highlights the gulf that can arise between a person and an AI due to the qualitatively different ways in which each produces an outcome. For example, a diffusion model for image generation transforms an image of statistical noise into a coherent image, an image creation process unfamiliar to most people. To bridge the Process Gulf, the paper proposes creating a simplified, separately derived, but controllable representation of the AI’s actual process, also termed a Surrogate Process. With a more accessible representation of the set of choices the AI needs to make in the process, the user can better intervene and guide the execution. Open question: since AI systems can be understood at many levels of abstraction, what’s the right level of explainability so that humans can easily understand and control how AI solves a problem?

4\ In-context evaluation and learning. Today, an AI tasked to recommend clothes you like would simply show you visuals of the clothes for at-a-glance evaluation. However, when the task becomes complicated, like creating code for an app, the AI system may provide comments, a natural language summary, or an architectural diagram of the code produced to help you evaluate. Future research: explore ways to provide simple, dynamic, and accessible explanations (e.g. visual, links to learn more) of the outcome produced would be useful for in-context evaluation and learning — it also assists with understanding the state of the problem after the AI performs some work, as the paper alluded to.

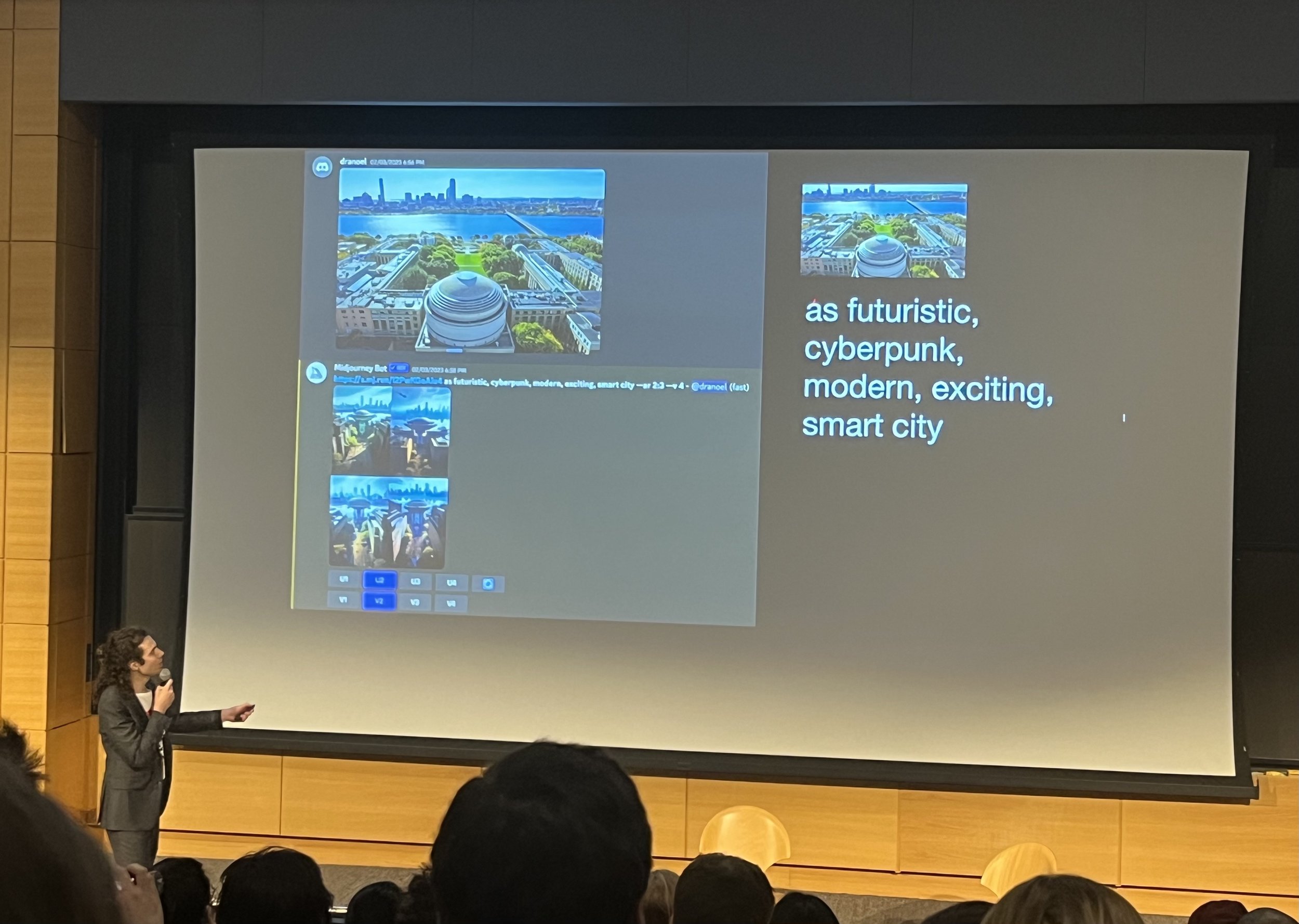

5\ Control mechanisms inspired by real-life tools. The importance of control mechanisms has been discussed extensively in the HCI community and I especially love the principles outlined in the People + AI Guidebook. When thinking about the appropriate levels of control, the common mechanism is providing parameters for a user to play with. For example, in Midjourney (a text-to-image model), users can adjust the “chaos” parameter to produce variations of the image. However, no support is currently provided to understand how a particular value will impact the generated images. Relatedly, as an interesting research exploration, PromptPaint provides users the ability to influence the text-to-image generation through paint medium-like interactions, using the paint palette metaphor to provide more control. As a result, it helps users specify their goals at greater granularity and gives users the ability to modify the choices involved as AI is producing the image. Future research: based on the specific task, what other real-life metaphors can be referenced as inspiration for control mechanisms (like pain palette for image generation)?

In Prompt Paint, the user can specify the area of generation with brushing (dark grey) with a prompt stencil. When the user completes brushing, the tool starts generating a part of the image while showing the process to the user (Chung and Adar, 2023)

6\ Interactive alignment for multi-users. The paper has been primarily discussing the user interface challenges and opportunities of a single user interacting with a single AI. As the paper alluded to, it would be useful to consider the alignment for interactions that include multiple parties, which introduces additional dimensions and complexity. For example, when an AI engaged in a music creation task involving two people. Future research: how would the alignment goals, processes, and dimensions evolve for a wider range of collaboration scenarios?

Thanks for reading

This post covers a broad set of themes in the AI alignment problem space. In upcoming HCI paper reviews, I’d love to explore specific use cases and verticals in the field. If you have any thoughts or suggestions, please leave a comment or get in touch!

Thanks to Bonnie Luo and Benjamin Yu for helpful discussions and feedback.

References

Jakob Nielsen. 2023. AI: First New UI Paradigm in 60 Years”. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ai-paradigm. Accessed: 2024-03-01.

John Joon Young Chung and Eytan Adar. 2023. PromptPaint: Steering Text-to-Image Generation Through Paint Medium-like Interactions. In Proceedings of UIST 2023. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 17 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3586183.3606777

Michael Terry, Chinmay Kulkarni, Martin Wattenberg, Lucas Dixon, and Meredith Ringel Morris. 2023. AI Alignment in the Design of Interactive AI: Specification Alignment, Process Alignment, and Evaluation Support. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.00710.